'I Wanted To Live The Life Of A Normal Kid,' Kamsky Says In Candid Interview About His Past

GM Gata Kamsky, a former FIDE world championship challenger and world number-four, spoke earnestly about his difficult past on Ilya Levitov's YouTube channel in an interview made available in English last week (originally recorded in October).

The most intimate topic was the strained relationship with his father, Rustam Kamsky. Although Rustam's actions have reached news headlines previously, Gata agreed to a two-hour conversation in which he provided troubling and, at times, horrific details about his early life.

The full interview is available below in Russian, but turn on captions for English translations.

Gata concluded, "Before, I may have not said so much, but I realize now that I'm older that it's important to tell people what happens behind the scenes." He went on, "I think it's important to discuss this topic, to talk about what stands behind every champion, the sacrifices they must make."

Before, I may have not said so much, but I realize now that I'm older that it's important to tell people what happens behind the scenes.

He also discussed various interesting topics, but they aren't the focus of this article. They include how he met his wife, WGM Vera Nebolsina, and moved to France, where they live; relationships with his mother and sister; his early trainers; winning the U.S.S.R. Junior Championships and moving to the United States in 1989, playing against greats such as GMs Garry Kasparov, Anatoly Karpov, Viswanathan Anand, Veselin Topalov, and Boris Gelfand in the 2011 Candidates, as well as players of the next generation like GMs Magnus Carlsen and Hikaru Nakamura. Other topics include taking a nearly decade-long break from chess to complete law school and also his views about online cheating.

Gata's interview was released in English shortly after 18-year-old World Rapid Champion Volodar Murzin shared the harrowing story of how he escaped from an abusive father. "He started beating me constantly when I was seven," Murzin told the Russian sports website Championat.

Please be aware this article contains details about trauma and abuse.

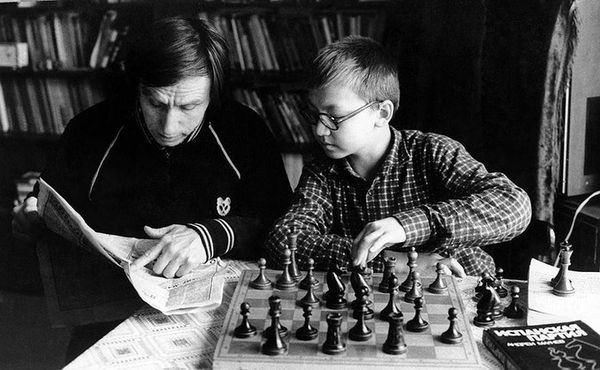

Rustam, once a professional boxer who spent several years in prison before becoming a photographer, had big plans for his son. The original plan was that Gata would become the next "Paganini," except on the piano, but when that fell through, Rustam found the alternative in the newspaper. Gata explains that one day, his dad asked, "What are you going to do to become famous and make money?" In the day's paper, Kasparov was playing Karpov for the world title. The father said, "Here's a young and famous person. Why not play chess?" Gata added, "Neither he nor I knew anything about chess."

So that's how it began, and Gata sacrificed his childhood years to study the game against his will: "I wanted to live the life of a normal kid. My father forced me to play chess, and he threatened me. I did what I could, I was on my own." He had nobody at home to turn to because when his parents split, they agreed that the mother would take his sister, and Gata would be left with Rustam.

I wanted to live the life of a normal kid. My father forced me to play chess, and he threatened me. I did what I could, I was on my own.

The only way he distracted himself besides chess was by running away into the world of books. His dad had a big library. But he didn't go outside and play with the other children.

His father beat him frequently, Gata recalled, and the father battled his own demons. At some point, he started drinking: "As I was told later, for people who were born after the war, it was a difficult time, and they didn't have a way to occupy themselves to forget about it. The only way was to drink."

When his dad was drunk one time, he said, "Talk to me the next time this happens, stop me." At first, his dad listened, but then he stopped and said Gata was too young to admonish him and punished him for it. It was a turning point: "I understood that when a father breaks his word, the person who is supposed to protect and to raise you, if this person breaks his word, what are you supposed to do?"

Gata beat GM Mark Taimanov at the 1987 Leningrad Championship, though the rest of the tournament didn't go well. He explained that he was analyzing a game with his early coach, Vladimir Shishkin, when his father stormed in and, in a fit of rage, threw a chair at Gata's face. Bleeding, he was rushed to a hospital. He told the doctor he fell.

Eventually, he told his school principal about the situation, and his dad was called in. When he returned home, Rustam turned on a hotplate and burned Gata's hand with it. He said, "The next time you complain about me, be prepared, I'll end you."

Gata became the U.S.S.R. junior champion at age 12 in 1987, and in 1989, he defected from the U.S.S.R. with his father when they left for the New York Open. Did he understand what a huge talent he was at the time, Levitov asked? Gata redirected the question: "When I played chess, I escaped the problems in my life. People used to laugh, why do I play on in lost positions for so long? It's because I didn't want to go home," where he would be punished for losing.

Chess wasn't something he studied out of love but out of compulsion. "To be honest, I didn't want to live sometimes. I felt like I wasn't a person, that I was an instrument to which someone could say, 'do this, do that.'"

To be honest, I didn't want to live sometimes. I felt like I wasn't a person, that I was an instrument to which someone could say, 'do this, do that.'

Gata worked hard on his chess in the 90s, living in the U.S. His motivation was freedom: "It occurred to me that the faster I become the world champion, the faster he'll leave me alone." He challenged Karpov for the FIDE world title in 1996. Karpov was the FIDE world champion, while Kasparov was the PCA world champion at the time. Karpov won the match against Gata 10.5-7.5.

There was a widely publicized scandal with GM Nigel Short in their 1994 PCA semifinal match. During game four, Gata had a cold and was coughing at the board. Short asked if he could refrain from coughing, and Gata said this distracted him; for the rest of the game, he was more focused on suppressing his cough than the position—and he lost. Rustam, when he learned of this, rushed to the restaurant and told Short, "If you do that again, I'll kill you."

"On the one hand, I understand this is awful, but on the other I was happy that Short understood what I'd been living with for the last 15 years, so that he could understand who my father was," Gata said. After this, Rustam wasn't allowed in the playing area or near Short. Gata won the match 5.5-1.5.

I was happy that Short understood what I'd been living with for the last 15 years.

Gata reiterated, "It meant nothing to me, to become a world champion or not. It was more important for me to become a normal person, a happy person." The first time he lived independently from his father was at the age of 30 when he got married. Chess didn't exactly bring him freedom as he had hoped.

In the interview, he reflected, "I think that a person, especially an adult, shouldn't have such great expectations on a child. If he has ambitions, he should fulfill them on his own."

I think that a person, especially an adult, shouldn't have such great expectations on a child. If he has ambitions, he should fulfill them on his own.